Sōkeiji Temple is a gorgeous temple located in Minato City, Tokyo Prefecture, and about a ten minute walk from Shirokane-Takanawa Station. On the way to the temple from the station, you may notice you are in a quieter part of Tokyo compared to the rest of the city, which is nice while considering what a temple is actually used for. We even had a chance to meet with Sōkeiji Temple’s chief priest, Taiju Sakamoto, and learn about the art of Japanese zazen.

The first thing I noticed was on the side of the main hall; there are three rows of miniature Buddha statues leading up to a larger Buddha playing with small children. I have actually seen multiple statues of Buddha playing with children.

After looking around outside for a bit, we stepped into the main hall. There I saw prayer mats, religious instruments, statues and more. I could smell the scent of incense burning and feel the spirituality in the air. It is wild to see people dedicating their whole lives to this, but some people think it is destiny, such as Chief Priest Taiju Sakamoto. So, without further ado, Chief Priest Taiju Sakamoto began teaching me the art of zazen.

The first step in meditation was to take off my shoes and socks. Once my feet were free, it was time to have a seat and cross my legs. I started out in a full-lotus, but I was told to make myself more comfortable and adjust into a half-lotus. From there, I put my left fingers over my right ones and touched my thumbs together to shape an egg with my hands. My back was not straight enough, so Chief Priest Taiju Sakamoto adjusted it for me. At this point in time, I was ready to begin meditation.

I closed my eyes, and started breathing. I was told the best way to breath is by slowly counting as I breathe. I took a slow, deep breath in, then exhaled while thinking, “1.” I followed this pattern with the subsequent numbers, and without realizing how focused my thoughts on counting were, I had forgotten about everything else on my mind; my mind was literally cleared, and my conception of time was lost.

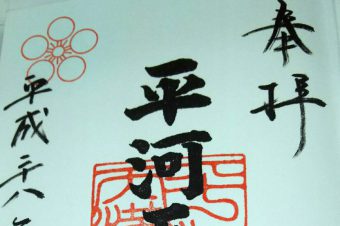

Once I got the breathing down, it was time to move onto the next step which I like to call the whacking stick, or more properly and correctly, the keisaku. The keisaku is the long, flat stick in the picture above. This keisaku is used to smack the back of someone meditating a total of four times in order to correct feelings of sleepiness or lapses of concentration. The wielder of the keisaku first smacks the meditator two times between the shoulder blade and spine, and then the meditator is quickly greeted with two more smacks between their spine and their other shoulder blade.

I got into position with my arms crossed and my body bent over with my back exposed and inviting; I was ready to receive my discipline and obtain ultimate concentration. I had never been hit with a keisaku, so I was not sure what to expect, but when the keisaku met my back, all I received was a mild sting, but I only felt it for a second. After was followed by another whack on the exact same spot, followed by two more whacks on the vertically opposite spot on my back. My concentration had been restored, and the meditation was complete. Afterwards I got to try whacking the stick myself, it was fun, but I was nervous about hitting another person with a wooden stick in the name of Buddha.

After meditation, we all prayed together. We lit some incense, and sprinkled some wood shavings on a charcoal burner to create a pleasant, smoky aroma. This is to create a spiritual connection between the people in the main hall. In Japan, the scent of incense has long been considered to connect people with each other; spiritual connections are very important in Buddhism, and in that moment we were all one.

After doing so, we took a seat and watched the chief priest preform a prayer. He used percussion instruments (known as Buddhist altar articles) to bang on while a mesmerizing sutra. The sutra sounded just like a song, and his rhythm was on point like Travis Barker.

This metal dish in the photo above is an incense holder used to keep track of time. One can keep track of time, using this dish by putting an incense stick in the top of it and lighting it up. However, there is a clock next to it now because things are naturally becoming more modernized, and a clock is a much more accurate way to keep track of time than by looking at an incense stick.

There is a sign in this temple with a sticker of praying hands on a rainbow flag placed on it. This signifies the temple does not care about race, religion, gender or sexual orientation; Buddhism does not judge you like that. At Sōkeiji Temple, absolutely everyone is welcome.

It is worth noting before you enter the temple there is a gate at the entrance called “Sanmon.” This gate marks the boundary between the temple and the mundane world. It is similar to a torii gate at a shrine where you separate the spiritual realm from the outside world. You must enter this gate with a feeling of quietness.

It was an honor to meet Chief Priest Taiju and learn zazen from him. He told me that doing it for only three minutes a day is good practice for a happy lifestyle. One of the differences between temples and shrines is the way they pray. At shrine, you clap twice; however, you do not clap when you pray at a Buddhist temple because the Buddha is already aware of your presence. You can learn how to pray here:

-340x226.jpg)