NEWS FLASH!

We interrupt the regularly scheduled programming to bring you this special bulletin.

On December 14th, crowds of history fans will descend upon Sengakuji Temple in Takanawa!

Here’s why:

SENGAKUJI TEMPLE AND THE AKOU INCIDENT

The 14th of December has special significance for the Japanese people. It is not a holiday, nor will most calendars have any special notation on that day. On this day, however, large numbers of people gather at Sengakuji Temple in Takanawa, near JR Shinagawa Station. Quite a few people can also be seen walking a 12-kilometer-long route from Ryogoku to Sengakuji Temple.

December 14th is known nationwide as Uchi-Iri-No-Hi, meaning “The Day of The Raid.” Which raid might they be referring to? None other than that of the 47 Loyal Retainers of Akou. In the U.S., the group is better known as The 47 Ronin. (Not to be confused with the movie of 2013, which has no similarity whatsoever to what actually happened other than using some of the names of people/places involved.)

Officially known as the Akou Jiken (Akou Incident), here is a very brief synopsis of what happened.

It was snowing on the night of 14-15 December, 1702. At about 3:30AM, 47 samurai stormed a residential compound in present day Ryogoku. They took the head of Minister Kouzukenosuke Kira, who was the Chief of Protocol at Edo Castle. This was to avenge the death of the Akou Liege, Lord Takuminokami Asano, who was forced to commit ritual suicide (seppuku, perhaps better known in the West as hara-kiri) after he attacked Minister Kira within one of the Edo Castle buildings almost two years previously.

(Note: about the snow. Japan used a lunar calendar during that era. December 14, 1702 would be equivalent to January 30, 1703 using a solar calendar. Hence the snowy night.)

Not so much these days, but while I was growing up in Japan, just about every year a new movie or TV series would come out, based on this famous incident which continues to hold the fascination of the Japanese. That said, in October 2016, to mark its 50th anniversary the National Theatre in Tokyo started a three month run of the celebrated kabuki show Kanadehon Chushingura (trans: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, and is a play somewhat loosely based on the Akou Incident) featuring all 11 acts. Not only is it rare for a theater to stage all 11 acts, but some of the biggest names in modern day kabuki were assigned the major roles. Important Safety Notice: some of the readers may run an internet search on Kanadehon Chushingura to find out the drama is set during a different era from the Akou Incident and none of the same names appear. Keep in mind the play originally opened during the Edo period. Fearing the Tokugawa Shogunate bureaucrats would shut the play down if real dates and names were used, the playwrights set the play about 400 years earlier than the incident and changed the names of all involved.

It took a lot of soul searching to figure out what to write about this famous episode in Japanese history. There are so many dramatic variations it is hard to sort out fact from fiction. Should I try and write a factual account? Or, what with me being a Navy man where it is often remarked “never let the truth interfere with a good sea story,” summarize some of the dramatic versions floating around? In the end, I decided to not present a shortened version of either the truth or popular dramas, but focus on how someone can experience part of that history for him/herself today.

If you are not familiar with the story, please run an internet search. To avoid all references to the movie, I recommend you use the search term “Chushingura.” This is the name given to semi-fictional accounts, such as puppet theater, kabuki plays, TV series and movies, of the 47 Loyal Retainers and the Akou Incident. (Running a search for 47 Ronin is not advised because of the recent movie.) The rest of this column will assume the reader has some familiarity with the Akou Incident.

However, just to show how all of the drama is not 100 percent manufactured for the stage or screen, here are two of the frequently appearing dramatic episodes which actually have some factual basis, and one “maybe.”

FICTION: In Chushingura, retainer Genzou Akabane brings along a jug of sake and pays a visit to his elder brother’s house on the day prior to the raid. Unfortunately, his brother is not there, so Genzou asks the household servant to place his brother’s montsuki (formal garment emblazoned with family crest) on a hanger. Genzou then places a sake cup in front of the coat, pours himself a cup, and tearfully holds a conversation as if talking to his brother for the last time.

FACT: There was a retainer named Genzou Akabane. Instead of his brother’s house, he visited the household which his younger sister married into. Although Genzou was a teetotaler, he plied his in-laws with sake and towards the end of the day stated he, too, felt like drinking some sake that day, and did. As Genzou still participated in the raid, one surmises he only took a few small sips.

FICTION: Also in Chushingura, Kuranosuke Ohishi, the leader of the 47 retainers, pays a visit to the house where Lord Asano’s widow, Lady Aguri, lived. This is on the day prior to the raid. He has brought along a blood pledge signed by the 47, which has their thumbprints, in blood, at the bottom of their respective names. What the retainers have pledged is they will avenge the death of Lord Asano, even if it costs them their lives. Ohishi is about to present this rolled document to Lady Aguri when he realizes one of the household servants is taking an undue interest in the affair. Correctly surmising this is a spy working for Lord Uesugi (Minister Kira’s biological son whom was adopted into the Uesugi family), Ohishi crafts up a tale about how he will soon enter the service of a distant warlord, has come to pay his last respects to Lord Asano, and desires to place a collection of haiku poems at the altar. Lady Aguri is outraged, denies Ohishi permission to pay respects at the altar and leaves the room. Ohishi pleads with Lady Aguri’s lady in waiting to at least accept the roll of haiku poems, in actuality the blood pledge, and place it at the altar. She takes pity on him and obliges him by placing the rolled document at the altar. As soon as Ohishi and his servant exit the main gate of the residence, Ohishi turns around, gets on his hands and knees on the ground in the snow, bows his head and pays his respects to Lord Asano. Later on that evening, the lady in waiting discovers the spy attempting to steal the rolled document. The spy is captured but commits suicide by biting through her tongue. The lady in waiting takes a closer look at the rolled document to find out it is actually a blood pledge, not a bunch of poems, and informs Lady Aguri. Lady Aguri regrets her temper tantrum and spends the rest of the night in front of Lord Asano’s altar, praying for a successful outcome.

FACT: In reality, Ohishi’s last visit with Lady Aguri took place over a year prior to the raid. He did, however, on the day prior to the raid, send Lady Aguri an accounting notebook which fully outlined all of the expenditures in support of the raid. It is surmised Ohishi felt he had to do this as some of the money came out of Lady Aguri’s dowry.

MAYBE TRUE: One supposedly factual episode, which doesn’t appear too often in these movies and dramas, takes place in Hakone. One of the retainers, Yogorou Kanzaki is rushing back to Edo (present day Tokyo) to participate in the raid. While crossing the Hakone Pass, he is accosted by a yakuza gangster running a horse scam. These gangsters force people to ride on the horses provided by the gang, and charge an exorbitant fee. Yogorou refuses and the gangster, thinking Yogorou is afraid of him, taunts him mercilessly. While it would have been extremely easy for Yogorou to draw his sword and lop off the gangster’s head, Yogorou doesn’t want to have any incident delay his arrival in Edo. The gangster agrees to let Yogorou go if Yogorou writes a formal apology, drops to the ground and kowtows. Yogorou submits and the two go to a nearby teahouse where Yogorou writes the formal apology and bows his head to the ground before setting off to Edo. Later, the gangster finds out about the Akou Incident, and realizes the samurai he taunted as worthless and weak was actually one of the 47 loyal retainers. The gangster is deeply shamed (and probably realized how close he came to a gruesome death, no doubt), leaves the gang, shaves his head and becomes a Buddhist monk.

This teahouse is still in business! It is located on the Old Tokaido Road leading up to Hakone from the Odawara side. Behind the teahouse one can see a section of the footpath which was the actual Tokaido back then. According to the teahouse’s website, every year on December 14th, from 7AM to 10AM, the teahouse offers free amazake to celebrate the event. Run an internet search for Amazake Chaya, there are plenty of English language sites featuring the place.

Now, back to Edo (Tokyo). How about experiencing this history for yourself? Obviously the easiest thing to do, and which I highly recommend, is to pay a visit to Sengakuji Temple, offer incense at the graves of the 47 loyal retainers, and pay a visit to the small museum located within the Sengakuji Temple grounds and dedicated to the Akou retainers. This can be done on any day, but doing so on either December 14 or 15 will have special significance.

For the hard-core enthusiast such as myself, the best thing to do is to retrace the victory path the retainers took after successfully avenging the Liege’s death. Yes, I am talking about walking the 12.2 kilometer route from Minister Kira’s residence to Sengakuji Temple, and specifically walking on the same calendar day as the raiders did. This will be December 14 for most people, December 15 for the hard core history enthusiast.

With the raid starting at 0330 on the night spanning 14-15 December, defeating Minister Kira’s security force took about half an hour. Then, it took about an hour to find Kira’s hiding place. With Kira’s detached head securely wrapped in fabric and hung from the end of a spear, the Akou retainers first went to take defensive positions at the foot of Ryogoku Bridge. They fully expected an Uesugi force to come after them. After a while, it was determined there was not going to be an immediate attack, so the Akou retainers embarked on their way to Sengakuji Temple, to place Kira’s head at their late Lord’s gravesite and announce they had avenged their liege’s death. Because crossing the Ryogoku Bridge would take the group through neighborhoods which were primarily samurai, they headed south to cross at the Eitai Bridge instead. Near the foot of the Eitai Bridge was a miso shop called Chikuma. The store people served the Akou retainers hot amazake that morning. According to the Chikuma store website, this was because the store’s first generation proprietor, Sakubei, belonged to the same haiku circle as one of the Akou retainers, Gengo Ohtaka.

You, too, can taste this amazake! As stated earlier, even to this day, on December 14th every year, crowds of people retrace the retainers’ steps from Ryogoku to Sengakuji. While the Chikuma miso shop has since moved to a new location, the store sends employees to its original location to serve hot amazake to these enthusiasts. Fortunately, Chikuma also details an employee on the 15th as well for the few people such as your humble scribe who prefer to make the trip on that day instead, because that is the date the retainers actually made the march. (Remember, the timing of the raid was set to take place after a tea party hosted by Kira on the evening of December 14. People making the trek during the day on the 14th are actually marching before the raid even took place.)

I made the march about three years ago, on the morning of December 15, naturally. Here are some pictures of notable locations en route.

The entrance to the Ryogoku memorial park/shrine dedicated to Minister Kira. This was part of his residential compound, and contains the well where the Akou retainers rinsed off Minister Kira’s severed head.

A statue of Minister Kira.

Chikuma amazake stand and memorial

I couldn’t find the memorial located somewhere on the grounds of St Luke’s International Hospital, located on the site of the Akou Fiefdom’s official residence, which is where the retainers briefly stopped and paid their respects. So I took a photo of this sign instead, just to show “I was there.” Hey, it was cold, raining, and I had to find a bathroom, fast.

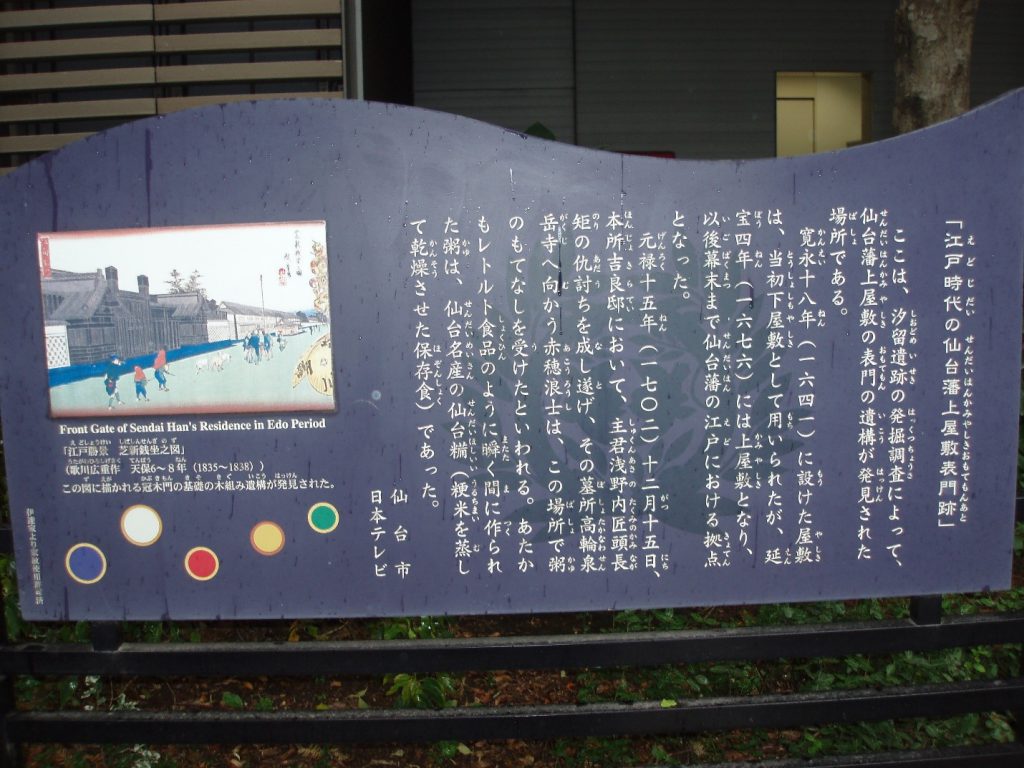

This is at Shiodome. The NTV building is located on the site of the Sendai Fiefdom official residence, which is where the Akou retainers were served some breakfast.

I’d just like to point out the memorial specifically says December 15th is when the loyal retainers stopped by.

A welcome sight! Sengakuji Temple’s gate!

A statue of Kuranosuke Ohishi, located at Sengakuji Shrine.

Out of respect, I do not take any pictures of graves, so you won’t find here any photos of the Sengakuji graveyard where the 47 are buried.

Instead, some interesting vignettes from that December 15th at Sengakuji.

I first noticed a group of about 30 people whom had obviously made the trek, and were coming together for a group shot in front of the Sengakuji gate. No one had a tripod, and they were about to takes turns with several people taking photos of the group. I offered to be their cameraman, and they accepted. Normally in such a situation I would say “Hai, cheezu!” so the people know when to smile, but this time I said “Yama!” instead. Everyone broke into huge smiles and responded with a resounding “Kawa!” and I took their photo. You see, yama (mountain) and kawa (river) were the now famous “challenge and reply” passwords used by the Akou retainers to identify themselves to each other as they dispersed throughout the dark confines of Minister Kira’s residence.

There in a section in the Sengakuji Temple graveyard dedicated to the Akou retainers. At its entrance is a little hut where one can buy bundles of incense to offer at the various graves. The staff also light the incense for you. As I joined the queue that day to buy incense, I noticed the comely young lady standing in line immediately in front of me. Despite the cold and drizzle, she was wearing short shorts and sheer stockings. Dressed for combat, perhaps? People usually start at Kuranosuke Ohishi’s grave to make the rounds of the 47 graves, and offer an incense stick at each grave. This particular lady gave one stick to Kuranosuke Ohishi, one stick to his son Chikara, then rushed over to Yasubei Horibe’s grave. Yasubei Horibe was the best swordsman amongst the 47 and famous in his own right. Anyway, the lady squatted down in front of Yasubei’s grave, offered him the rest of her bundle of incense, and bowed her head in deep prayer. I’m sure Yasubei was mightily pleased.

Now, a short introduction about Sengakuji Temple. Sengakuji has the distinction of being the ONLY temple founded by Shogun Ieyasu Tokugawa. While there are numerous temples patronized by Lord Ieyasu, or which inter his soul or remains, Sengakuji is the only temple which Lord Ieyasu personally founded.

Now, one might ask why would Lord Asano, who incurred the wrath of Fifth Shogun Tsunayoshi Tokugawa, be buried in a temple so important to the Tokugawa family. Well before the Akou Incident, Sengakuji burned down in a fire and the Akou Fiefdom was tasked with rebuilding the temple. Sengakuji therefore became the family temple for the Asano family, which is why Lord Asano was interred there.

The 47 retainers are buried in a separate compound adjacent to Lord Asano’s grave. Kuranosuke Ohishi’s tombstone is easy to find, it’s the only one which had a wooden structure over it. The rest are fully exposed to the elements. Each tombstone bears the specific retainer’s Buddhist name. Interestingly, each name shares the same first and fourth kanji characters. Taken together, the two characters mean “walked on the cutting edge of a sword,” implying the retainers achieved the impossible. Each retainer is buried in seated fashion, holding his severed head in his lap.

Being of a military background, one of my favorite souvenirs to take for my military buddies back in the US is the victory omamori (good luck charm) issued by Sengakuji. The omamori features the Ohishi family crest, and is reputed to help you achieve success.

Leaving Sengakuji, one notices the busy multi-lane boulevard about 50 meters down the slope. This is the #1 Keihin, or National Route 15. However, back during the Edo period, this was the Tokaido linking Edo to Kyoto. Now, to enter Edo proper a traveler had to pass through one of the Daikido (large wooden doors) leading into the city. These gates were closed at night. The Daikido guarding access from the Tokaido was originally located at present day Fuda-no-Tsuji (near JR Tamachi station), constructed in 1616, and named the Shibaguchimon. In 1710 (about eight years after the Akou Incident), the gate was moved approximately 700 meters south to very near Sengakuji, and renamed the Takanawa Daikido. People from all over western Japan, when entering Edo, would have to spend some time waiting to gain access through the Takanawa Oh-mon. Right up the street would be Sengakuji, so why not kill some time by visiting this temple where the famous 47 loyal retainers are interred? This plan was a success and the temple prospered.

There are two reasons why the Tokugawa Shogunate desired people visit Sengakuji. First, of course, was financial. All of these tourists would provide the obligatory monetary offerings, probably buy omamori, etc., and the temple would be financially secure. More important, however, was the Tokugawa Shogunate really started pushing the concept of “absolute loyalty” around that timeframe Keep in mind this was during a period of “sea-change” when Shogun Tsunayoshi was converting his government from military mindset to civil mindset. Shogun Tsunayoshi also wanted to shift the basis for promotion from the vestiges of battlefield prowess (i.e. killing people) to loyal service. He is often criticized for introducing the “Take Pity on Living Things” law, under which people were forbidden to take the lives of animals and even imprisoned/exiled for transgressions. However, it is believed Shogun Tsunayoshi desired to stress the sanctity of life with this law. Up until then, there wasn’t much value placed on human life either. Samurai would routine kill innocent passersby for sport or to merely test their swords. If killing people still meant promotion, then it would only be a short leap to consider starting a coup d’état against the Tokugawa government. So, Shogun Tsunayoshi (who passed away in February 1709) and his successor Shogun Ienobu wanted to stress the concept of absolute loyalty, especially to one’s liege. Hence, the example of the 47 loyal retainers as a sterling example of loyalty and the highest samurai ideals. Moving the Daikido meant people from all over Japan would see the graves, go back to their respective provinces and spread the tale of the 47 loyal retainers and the concept of absolute loyalty to one’s liege. The lieges in turn will be absolutely loyal to the Shogun himself.

Considering the esteemed place the 47 Loyal Retainers still hold in the hearts and souls of most Japanese, more than three hundred years later, I would say Shogun Tsunayoshi and Ienobu’s plan succeeded beyond their wildest imaginations.

William J. Young Jr. (Bill)

Born and raised in Kamakura, Japan, Bill Young is a former U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander who drove ships all around the Pacific Ocean and beyond. He was a U.S. Navy designated Anti-Terrorism Training Officer and spent two years in Southeast Asia, ensuring the safety of U.S. Navy ships, aircraft, and personnel. Based on the foundation of 20 years of service in the military, he now considers terrorism from the perspective of the average Japanese citizen and teaches, in Japanese, anti-terrorism measures, personal security measures, and information security practices to firms and individuals with vested interests overseas. Please visit http://www.rhumbline.co.jp/ for more information.